A new study evaluated the impact of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) and laparascopic adjustable gastric banding (LAGB) on bone health in type 2 diabetes patients. The study, “Effects of Gastric Bypass and Gastric Banding on Bone Remodeling in Obese Patients with Type 2 Diabetes,” was published in The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism.

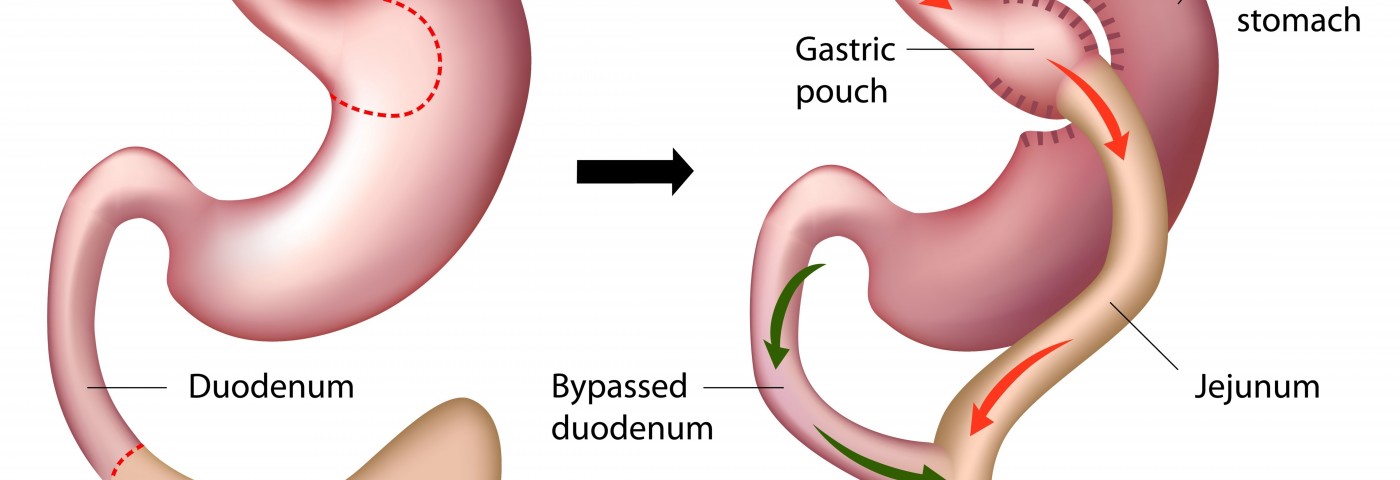

Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) and laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding (LAGB) are effective bariatric procedures for weight management. RYGB is considered “metabolic” surgery, involving hormonal alterations that lead to greater improvements in body weight and obesity comorbidities than LAGB, which is solely a restrictive procedure.

Bariatric procedures may unintentionally cause metabolic bone disease. RYGB is known to lead to a decline in bone density of 5% to 10% at the hip and 3% to 6% at the spine within the first year or two after surgery. The LAGB procedure has fewer findings concerning bone changes and those that exist show varied results. A large fraction of patients being submitted to bariatric surgery have type 2 diabetes (T2DM), a condition associated with structural bone defects and a 70% increased risk of fracture, so it is important to characterize the skeletal consequences of bariatric surgery procedures in this population.

Researchers prospectively evaluated the different effects of RYGB and LAGB on fasting and postprandial (after meal) indices of bone remodeling in adults with type 2 diabetes. A subgroup of participants had been enrolled in the Surgery or Lifestyle with Intensive Medical Management of type 2 Diabetes (SLIMM-T2D) trials was included in the present study. The participants were adults 21–65 years old with type 2 diabetes and a BMI of 30–45 kg/m2 recruited as part of two parallel, randomized controlled trials (ClinicalTrials.gov #NCT01073020). The researchers focused on individuals in the surgical arms of these trials who also participated in a mixed meal tolerance test (MMTT) sub-study (RYGB n= 11, LAGB n= 8). The MMTT is frequently used in the U.S., and is a liquid meal (Sustacal/Boost) ingested in the fasting state with timed measurements of C-peptide, which gives a direct measurement of pancreatic β-cell function.

Also evaluated were postoperative change in serum type 1 cross-linked C-telopeptide (CTX), a product of type 1 collagen degradation and a marker of bone resorption, and serum procollagen type 1 N-terminal propeptide (P1NP), considered a key marker of bone formation. Participants were checked at baseline (14 days or less before surgery) and at 10 days and one year after surgery.

RYGB was found to lead to an early and weight-loss independent increase in the CTX, a marker of bone resorption, as well as bone formation (P1NP) over a one-year period, whereas LAGB did not affect indices of bone remodeling among adults with type 2 diabetes. The elevation in CTX after RYGB is independent of weight loss or changes in intact parathyroid hormone (PTH), and may be associated with changes in peptide YY (PYY), an anorexigenic hormone secreted during feeding that increases after RYGB.

Future studies should further investigate connections between gastrointestinal hormones and bone as a potential mechanism of skeletal changes after RYGB surgery, researchers said.

The authors wrote, “In contrast to neutral effects of LAGB on bone, RYGB increases bone resorption markers soon after surgery, and in a manner that persists over at least 1 year. … The lack of change in biochemical parameters of bone metabolism after LAGB is perhaps reassuring in terms of the impact of this procedure on bone health.”

Finally, they stressed the importance of performing large prospective studies to examine differential changes in bone density after bariatric surgery. These studies will provide clinically important information for physicians and patients considering the potential risks of these highly effective weight loss surgeries.