A team of investigators led by Dr. Eric Belin de Chantemele, a physiologist in the Department of Physiology at the Medical College of Georgia at Georgia Regents University, have found that while high levels of the satiety hormone leptin don’t help obese individuals lose weight, they do appear to directly contribute to obesity-associated cardiovascular disease.

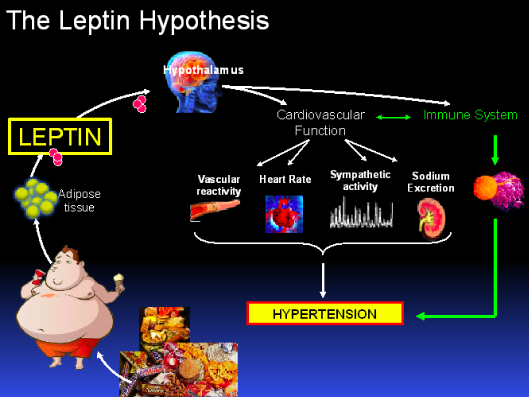

“With obesity, leptin cannot tell our brain to stop eating, but it can still tell our brain to increase the activity of the cardiovascular system,” Dr. Belin de Chantemele explains in a GRU release.

The main focus of Dr. Belin de Chantemele’s laboratory team at Georgia Regents University is to understand how metabolic dysfunctions — and more specifically how obesity — affects the cardiovascular system to trigger hypertension. “In the lab, we are mostly interested in determining how leptin, a hormone secreted by the adipose tissue, is involved in the control of the cardiovascular function,” Dr. Belin de Chantemele observes. “The increase in adipose mass associated with obesity leads to an increase in leptin levels that is further exaggerated by the development of a gradual leptin resistance. Besides controlling food intake and energy expenditure, leptin exerts pleiotropic effects on cardiovascular organs either via an increased activation of the sympathetic nervous system or through a direct activation of the leptin signaling pathway in the vasculature, the kidneys and the heart.”

“Furthermore,” Dr. Belin de Chantemele continues, “in parallel to the control of the metabolic and cardiovascular systems, leptin also regulates the immune system that has recently been identified as a key player in the development of hypertension and vascular dysfunction. In the laboratory, we are testing the hypothesis that obesity triggers cardiovascular dysfunctions via an excessive activation of leptin signaling pathway. Our goal is to use an integrative approach to analyze the interaction between leptin and these different systems.”

In order to test the role of leptin in the control of the cardiovascular function, the laboratory is using a lean mouse model hypersensitive to leptin due to the deletion of the protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B (PTP1B), a molecular brake on the leptin signaling pathway. The investigators recently reported that increasing leptin sensitivity in lean mice triggers hypertension. Their main project consists in identifying the mechanisms involved in the development of hypertension by looking at the interaction between leptin, the sympathetic nervous and the immune system. Since most of leptin effects are mediated through a central activation of the pro-opiomelanocortin expressing neurons, the scientists are also studying the cardiovascular consequences of a specific increase in leptin sensitivity in pro-opiomelanocortin neurons.

In both cell culture and animal models, the researchers have shown that fat-derived leptin directly activates aldosterone synthase expression in the adrenal glands, resulting in production of more of the steroid hormone aldosterone. High aldosterone levels are known to contribute to widespread inflammation, blood vessel stiffness and scarring, enlargement and stiffness of the heart, impaired insulin sensitivity and other complications.

Aldosterone, which is produced by the adrenal gland, also has a direct effect on blood pressure by regulating salt-water balance in the body. High are an obesity hallmark and a leading cause of metabolic and cardiovascular problems. However the precise mechanism of how aldosterone levels become elevated in obesity had been a mystery.

“Identifying the direct connection of high levels of aldosterone and leptin make either a good treatment target to help avoid cardiovascular disease in obesity,” the GRU researchers write in the American Heart Association journal Circulation, explaining that their laboratory studies indicate that targeting either disconnects the link and associated cardiovascular problems.

Image Credit Georgia Regents University

The Circulation article, entitled: “Adipocyte-Derived Hormone Leptin is a Direct Regulator of Aldosterone Secretion, Which Promotes Endothelial Dysfunction and Cardiac Fibrosis,” (Published online before print September 11, 2015, doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.018226) is coauthored by Anne-Ccile Huby, Galina Antonova, Jake Groenendyk, Jessica A. Filosa, and Dr. Eric J. Belin de Chantemele, of the Medical College of Georgia at Georgia Regents University at Augusta, Georgia; Celso E. Gomez-Sanchez of the G.V. (Sonny) Montgomery VA Medical Center and University of Mississippi Medical Center at Jackson, Mississippi; and Wendy B. Bollag of the Medical College of Georgia at Georgia Regents University, Augusta, and the Charlie Norwood VA Medical Center, at Augusta, Georgia.

The article coauthors write that in obesity, excessive synthesis of aldosterone contributes to the development and progression of metabolic and cardiovascular dysfunctions, while obesity-induced hyperaldosteronism is independent of the known regulators of aldosterone secretion, but reliant on unidentified adipocyte-derived factors. The investigators hypothesized that the adipokine leptin is a direct regulator of aldosterone synthase (CYP11B2) expression and aldosterone release and promotes cardiovascular dysfunction via aldosterone-dependent mechanisms.

They conclude that Leptin is a newly described regulator of aldosterone synthesis that acts directly on adrenal glomerulosa cells to increase CYP11B2 expression and enhance aldosterone production via calcium-dependent mechanisms. Furthermore, leptin-mediated aldosterone secretion contributes to cardiovascular disease by promoting endothelial dysfunction and the expression of pro-fibrotic markers in the heart.

“There are already drugs out there that could work, including the old blood pressure drug, spironolactone, that directly targets aldosterone but is rarely used as a frontline blood pressure therapy,” observes Dr. Belin de Chantemele. “Spironolactone, a diuretic, helps the kidney eliminate water and sodium but hold onto valuable potassium, according to MedlinePlus. One way it works is by blocking the receptor to which aldosterone binds. There are also leptin receptor blockers under study for a wide range of problems from obesity to cancer.”

“It seems a bit of physiological irony that fat makes leptin,” he continues. In fact, fat from a woman makes even more leptin than the exact same amount of fat from a man, although why remains another mystery. Either way, obese individuals become insensitive to leptins impact on their metabolic, but not their cardiovascular system. Exactly why the brain becomes insensitive to the metabolic effect is yet another mystery, although there are theories about dysfunctional signaling and resistance by the protective blood-brain barrier to letting leptin in.”

Dr. Belin de Chantemele’s interest in leptin as an aldosterone trigger was piqued by a 1999 German study showing that something in fat cells, or adipocytes, was stimulating aldosterone. That obese individuals have high levels of both aldosterone and leptin has long been known, and by studying mouse models with severe endothelial dysfunction, stiff blood vessels and fibrotic hearts, he began to put the two together, observing that these mice, unsurprisingly, had high levels of aldosterone and were also hypersensitive to leptin.

Based on those conclusions, the research team went back to cell culture, loading increasing doses of leptin on adrenal cells, and observing increased aldosterone levels as a result. However, when they inhibited the leptin receptor, the increases didn’t happen. In subsequent studies in fat and lean mice alike the association kept showing up, ergo: the higher the leptin dose, the higher the aldosterone level. When the researchers used hormone inhibitors already associated with aldosterone, such as angiotensin II, leptin still increased aldosterone. One exception was that fat mice deficient in leptin receptors did not experience high levels of aldosterone. “Its clearly a direct link between leptin and aldosterone,” Dr. Belin de Chantemele maintains.

Next up, the researchers want to see how well the link holds in humans. Dr. Belin de Chantemele with colleagues Dr. Thad Wilkins, a professor in the Medical College of Georgia Department of Family Medicine, and Dr. Miriam Cortez-Cooper, associate professor in the

Next up, the researchers want to see how well the link holds in humans. Dr. Belin de Chantemele with colleagues Dr. Thad Wilkins, a professor in the Medical College of Georgia Department of Family Medicine, and Dr. Miriam Cortez-Cooper, associate professor in the  GRU Department of Physical Therapy, are starting to look at leptin-aldosterone interaction and levels in 40 overweight men and women who are not taking any cardiovascular medication. They have early evidence, in humans and animals, that the correlation will be strongest in the females, who make so much more leptin.

GRU Department of Physical Therapy, are starting to look at leptin-aldosterone interaction and levels in 40 overweight men and women who are not taking any cardiovascular medication. They have early evidence, in humans and animals, that the correlation will be strongest in the females, who make so much more leptin.

“We want to see if we can confirm what we are seeing in mice in the human population,” Dr. Belin de Chantemele notes. “If we see that, that probably tells us a blocker of aldosterone action, such as spironolactone, would be a good treatment particularly for obese females.”

He notes that high aldosterone levels in obesity are not associated with the usual suspects: angiotensin II, a hormone known to constrict blood vessels; the steroid hormone cortisol; and the adrenocorticotropic hormone, or ACTH, all are known to control aldosterone secretion. “In fact, obesity is often associated with low or usual levels of all these,” Dr. Belin de Chantemele explains.

The research was funded by a Scientist Development Grant from the American Heart Association.

Sources:

Georgia Regents University

Medical College of Georgia

Circulation

Image Credits:

Georgia Regents University