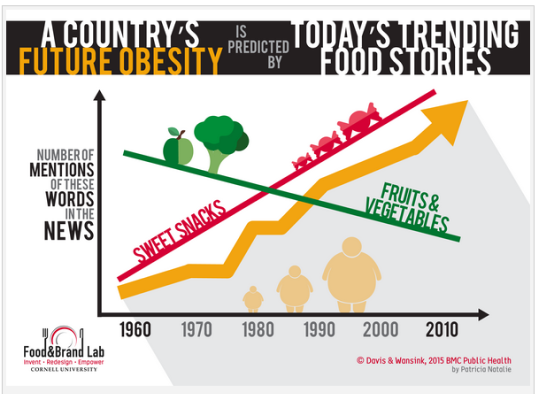

What you read today in news and information media is an accurate predictor of whether a country will be slimmer or fatter in three years time, according to a new study. A scientific analysis by researchers at the Cornell University Food and Brand Lab, whose mission is “To discover and disseminate transforming solutions to eating problems,” reviewed 50 years of key “food words” mentioned in major newspapers like the New York Times and London Times, and found that food words trending today in 2015 are a predictive of what a country’s obesity level will be in three years time, i.e.: 2018.

“The more sweet snacks are mentioned and the fewer fruits and vegetables that are mentioned in your newspaper, the fatter your country’s population is going to be in three years, according to trends we found from the past fifty years,” says lead author, Brennan Davis, an Associate Professor of Marketing from California State University at San Luis Obispo. “But the less often they’re mentioned and the more vegetables are mentioned, the skinnier the public will be.” Dr. Davis is Associate Professor of Marketing at California Polytechnic State University’s Orfalea College of Business, where he specializes in connecting large datasets to answer questions in the domain of transformative consumer research. Professionally, Dr. Brennan’s scholarly interest in transformative consumer research is reflected in his current research on marketing and obesity.

This study, published in the journal BMC Public Health, analyzed all of the different foods mentioned in stories in the New York Times and the London Times, and statistically correlated them with each country’s annual Body Mass Index, or BMI — a measure of obesity. While the number of mentions of sweet snacks were related to higher obesity levels three years later, the number of salty snack mentions were unrelated. The number of vegetable and fruit mentions were related to lower levels of obesity three years later.

“Newspapers are basically crystal balls for obesity,” says study coauthor, Brian Wansink, John S. Dyson Professor of Marketing and Director of the Cornell Food and Brand Lab in the Department of Applied Economics, Management at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York. Dr Wansink is also author of the book, “Slim by Design: Mindless Eating Solutions for Everyday Life“ . “This is consistent with earlier research showing that positive messages: ‘Eat more vegetables and you’ll lose weight’, resonate better with the general public than negative messages, such as eat fewer cookies.”

The investigators conclude that predicting a country’s obesity levels in three years might be easily done today using a newspaper. These findings provide public health officials and epidemiologists with new tools to quickly assess the effectiveness of current obesity interventions. If we wish to estimate obesity rates in three years, the best indicator will be what is mentioned in the paper today.

Dr. Wansink notes that every time media like the New York Times or the London Times mentions sweet snacks in news stories or commentary, it positively relates to how fat the US or UK will be three years from now. Conversely, every time they mention vegetables, it negatively relates to how fat these countries will be in three years time.

Results of Drs. Brennan’s and Wansink’s study are published in an Open Access research article by BioMedCentral Public Health, entitled “Fifty years of fat: news coverage of trends that predate obesity prevalence“ (BMC Public Health, 2015; 15 (1) DOI: 10.1186/s12889-015-1981-1)

The coauthors observe that in both the United States (US) and the United Kingdom (UK), rates of obesity among adults has risen, from 13.4% in 1960 to 33.8% in 2010 in the US and from 15 % in 1993 to 25.4 % in 2010 in the U.K., and that while people generally expect media mentions of health risks like obesity prevalence to follow health risk trends, food consumption trends may actually precede obesity prevalence trends. Consequently, their research investigates whether media mentions of food predate obesity prevalence.

The investigators reviewed fifty years of non-advertising articles in the New York Times (and 17 years for the London Times) which were coded for mention of less healthy (5 salty and 5 sweet snacks) and healthy (5 fruits and 5 vegetables) food items by year and then associated the data compiled with annual obesity prevalence in subsequent years using time-series generalized linear models test whether food-related mentions predate or postdate obesity prevalence in each country.

Drs. Brennan and Wansink discovered that United States obesity prevalence is positively associated with New York Times mentions of sweet snacks and negatively associated with mentions of fruits and vegetables, and similar correlations were are found for obesity levels in the United Kingdom cross-referenced to food articles in The London Times, noting that importantly, the obesity followed mentions models are stronger than the obesity preceded mentions models.

Based on their findings, the researchers conclude that it may be possible to estimate a nation’s future obesity prevalence (e.g., three years from now) based on how frequently national media mention sweet snacks (positively related) and vegetables or fruits (negatively related) today, and this may provide public health officials and epidemiologists with new tools to more quickly assess effectiveness of current obesity interventions based on what is mentioned in the media today.

Drs. Brennan and Wansink maintain that if the culture has become increasingly obsessed with sugary foods and less enthusiastic about vegetables during the same time, these trends would be reflected in the number of news stories mentioning them; and if the trends in obesity prevalence follow cultural food trends, then there would be a positive association between news stories of sugary foods and higher obesity prevalence and a negative association between news stories of vegetables and higher obesity prevalence. Therefore, fifty years of newspaper articles would be a valuable public record of cultural trends that predate the obesity rise. And because many social and cultural trends can quickly change, media mentions of foods and how they fit in current trends could foreshadow the movement in obesity trends in upcoming years.

The investigators observe that in their study changes in article mentions were compared to obesity prevalence patterns in the US from 1960 (the first year both US obesity prevalence and New York Times media mentions were available) to 2010 (i.e., fifty years) and in the UK from 1993 (the first year both UK obesity prevalence and London Times media mentions were available) to the same year, 2010. And while these newspapers are not fully representative of their countries, they are nevertheless influential and the only ones where all issues were fully-indexed online and available over a significant time period.

Fruit and vegetable mentions in the two papers were examined as two primary categories of healthy foods, and sweet and salty snack mentions as two primary categories of unhealthy food. To determine the four categories that represent food consumption extremes fruits, vegetables, sweet snacks, and salty snacks the researchers relied on reports from government agencies to determine which foods belong to each category. For example, the United States Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) most recent report on agricultural consumption listed the top five fruits consumed in the US — oranges, apples, grapes, bananas, and pineapples — and the top five vegetables — lettuce, corn, onions, carrots, and cucumbers. The United States Department of Commerce (USDC) listed the top five sweet snack food transactions in the US — cookies, chocolate, candy, cake, and ice cream — and the top five salty snack foods — potato chips, tortilla chips, crackers, popcorn, and pretzels. Since items like pretzels and crackers could be perceived as either sweet or salty, analyses were conducted with and without each item, and results did not differ. Actual obesity prevalence in the United States came from waves of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey published by the National Center for Health Statistics for select years from 1960 to 2010.

Similar GLM analyses were employed using London Times article mentions and obesity outcomes in the UK, using the top snack items because they differed from the US in name only while top fruits and vegetables differed in actual foods consumed. Actual obesity prevalence in the UK came from the National Health Service Health Survey, Department of Health (2011).

The researchers found that articles mentioning vegetables declined by 46 percent, and articles mentioning fruits, salty snacks, and sweet snacks increased by 92 percent, 417 percent, and 310 percent respectively over the last 50 years in the New York Times. Actual US obesity prevalence rose from 13.4 percent to 33.8 percent over fifty years.

Obesity prevalence was significantly associated with lower percentage of articles mentioning vegetables and fruits, and was also significantly associated with a higher percentage of articles mentioning sweet snacks. Obesity prevalence was not significantly associated with the percentage of articles mentioning salty snacks between 1960 and 2010.

The coauthors acknowledge that this study has limitations worth discussing, notably that it makes no claims of causality as an inherent limitation of analyzing secondary data. However, they maintain that it does present models where obesity prevalence follows versus precedes media trends to see which explains more variance, and could be valuable to the medical and public health community in helping them analyze and adjust public health messages and interventions, and that since few research measures exist from the earlier decades when obesity prevalence grew most rapidly, this analysis of newspaper articles over 50 years may provide valuable insights to help combat obesity in the future, providing public health officials and epidemiologists with new tools to more quickly assess the effectiveness of current obesity interventions.

The study was self-funded by the Cornell Food and Brand Lab.

Sources:

Cornell Food and Brand Lab

BMC Public Health

Image Credits:

Cornell Food and Brand Lab

California Polytechnic State University