Standing for a quarter or more of each day’s waking time is associated with reduced odds of obesity, according to the results of a recent study published in Mayo Clinical Proceedings. In the Cooper Center Longitudinal Study, the researchers also found that the inverse relationship of standing to obesity and metabolic syndrome is even more robust when combined with leisure-time physical activity.

The increased use of motorized transportation and more sedentary home and work lifestyles have, over the past several decades, resulted in a major reduction in daily energy expenditure among people in developed and developing countries. With the aim of examining the associations between obesity, metabolic syndrome, and standing time (independent of leisure-time physical activity), the research team led by Dr. Kerem Shuval, director of Physical Activity & Nutrition Research at the American Cancer Society, recruited 7,075 adults ages 20-79 who were attending Cooper Clinic (Dallas, Texas) for a preventive medical visit. All participants were enrolled in the Cooper Center Longitudinal Study (CCLS) and assessed for obesity status (body mass index ≥30), body fat percentage (men: ≥25%; women ≥30%), elevated waist circumference (men: ≥102 cm; women: ≥88 cm), and metabolic syndrome (yes/no). The study is titled “Standing, Obesity and Metabolic Syndrome.”

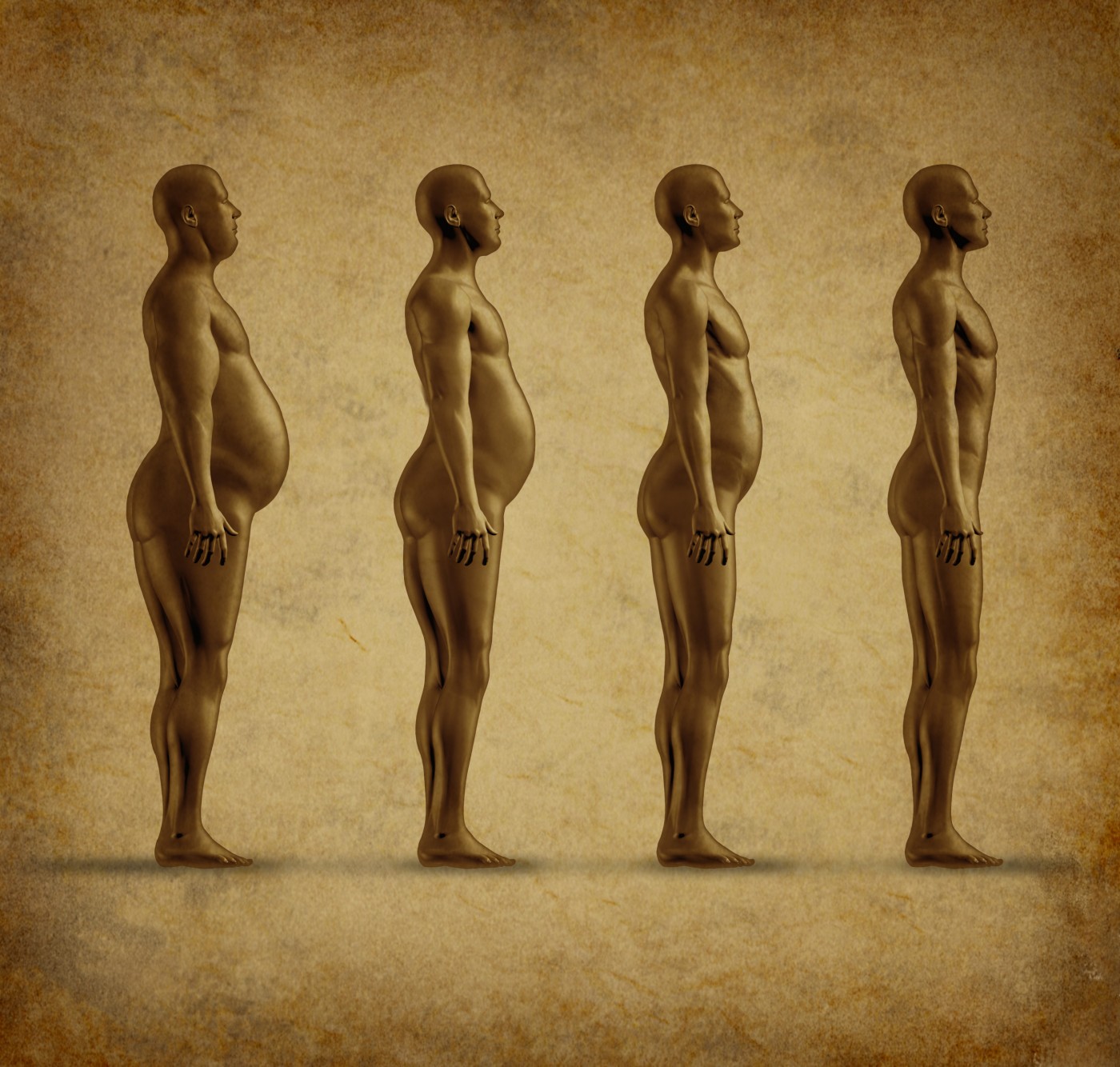

Results revealed that standing a quarter or more of time each day was associated with a reduction in the likelihood of an elevated body fat percentage in men, and with reduced odds of obesity and abdominal obesity in women. In comparison with the reference group of participants (those standing almost none of the time), women and men who met the physical activity guidelines were — with incremental additions of standing time — less likely of having all obesity outcomes and metabolic syndrome.

The study’s findings provide evidence regarding the protective effects of standing. However, the team of researchers cautioned that results should be understood in the context of the study’s limitations. Firstly, the research was cross-sectional, so it is unclear whether less standing leads to more obesity or whether obese individuals simply stand less. Secondly, while obesity and metabolic syndrome were empirically assessed, standing and physical activity were not, as the assessment of these variables was based on the participants’ responses, which may overestimate these behaviors.

Furthermore, the survey assessment used in the study did not ascertain whether participants were standing still or standing and moving. Standing and moving provides extra energy expenditure, but standing still is comparable to sitting in terms of energy expenditure.

Still, the researchers concluded: “From the joint association analyses underscore the potential protective health benefits from meeting the physical activity guidelines and increasing standing time. Thus, clinicians and public health practitioners should consider encouraging patients to achieve the physical activity guidelines and increase standing time for chronic disease prevention.”