A new study entitled “Weight Loss and Health Status 3 Years after Bariatric Surgery in Adolescents,” recently published in The New England Journal of Medicine and presented at the Obesity Society’s Annual meeting in Los Angeles, California, revealed that bariatric surgery led to substantial improvements in adolescents’ weight, metabolic health, and quality of life.

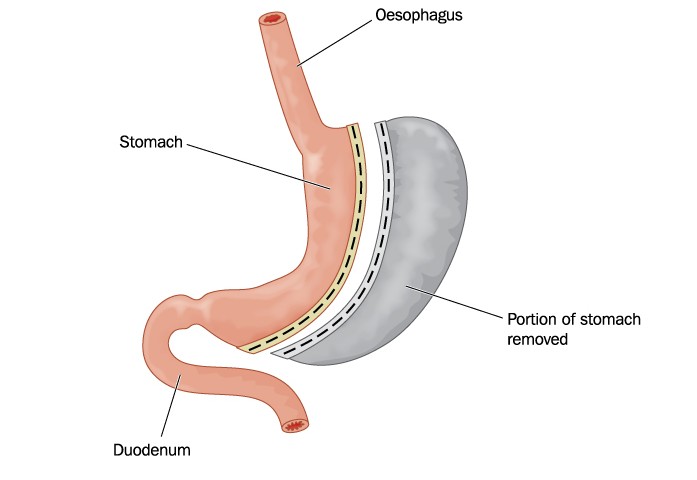

The study was conducted by the Teen-Longitudinal Assessment of Bariatric Surgery (Teen-LABS), a consortium made up of five clinical centers and a data coordinating center. The Teen-LABS study framework was developed by the LABS consortium, a group of surgeons, physicians and scientists dedicated to studying adult bariatric surgical outcomes. Bariatric surgery is a weight loss surgery where the size of the stomach is reduced with a gastric band or through removal of a portion of the stomach, or by resecting and re-routing the small intestine to a small stomach pouch (gastric bypass surgery).

The study recruited 242 adolescents aged between 13 to 19 years old who were all severely obese with an average weight of 325 pounds before surgery. The participants had an average body mass index (BMI) of 53 kg/m2. Three years after surgery, the research team found that the average weight of the participants had decreased more than 90 pounds (27%). The majority of participants showed reversal of obesity-related health problems: 95% reversed type 2 diabetes, 85% had normal kidney function, 74% had normal hypertension, and had 66% corrected lipid abnormalities. Notably, previous studies have shown that only 2% of severely obese teenagers could lose weight if not submitted to bariatric surgery.

Dr. Thomas Inge MD, PhD, lead author of the study, said that for adolescents the diabetes and hypertension disappearance rates are higher than those seen in adults that have been obese for a long time before bariatric surgery. If weight loss is maintained in teen patients, it may also lead to fewer strokes, heart attacks and other disabilities later in life. He added that the sooner doctors intervene in obese teens, the better the outcomes will be.

The study also evaluated nutritional and other risks associated with surgery, such as iron levels in the body. Three years after the surgery, more than 50% of the participants had lower iron levels then before the surgery. This finding supports the importance of monitoring and supplementing patients after undergoing bariatric surgery with vitamins and iron. In addition, 13% of patients were submitted to additional abdominal surgery such as gallbladder removal during the three year period.

Dr. Michael Helmrath, co-author and adolescent bariatric surgeon at Cincinnati Children’s, said that when teenagers reach high levels of obesity, only 25% can reach normal weights after surgery, and more than 50% of them remain severely obese even after surgery. He added that the timing of surgery may be crucial.

The researchers acknowledge the observational nature of the study and the fact that the majority of the participants were Caucasians. Importantly, they stress the importance of longer follow-up of adolescents who were submitted to bariatric surgery, since some of the observed health improvements may decrease with time and other health risks could emerge later.

Dr. Stavra Xanthakos, co-author and pediatric gastroenterologist at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, concluded that this type of long-term study will help pediatricians and obese teenagers and their families make informed and objective decisions about bariatric surgery, taking into account the benefits and risks.