Bariatric weight-loss surgery, in addition to aiding in weight reduction, may also curb cravings for sweets by acting on the brain’s reward system, according to new research reported in the journal Cell Metabolism.

The study, led by John B. Pierce Laboratory Associate Fellow and Yale School of Medicine Associate Professor of Psychiatry Ivan de Araujo, found that gastrointestinal bypass surgery, which is used to treat morbid obesity and diabetes, also reduced sugar-seeking behavior in mice by slowing the release of dopamine, a neurotransmitter that helps control the brain’s reward and pleasure centers and also acts to regulate movement and emotional responses. It suggests that positive outcomes of weight loss surgery are more likely because sugary foods seem less rewarding after the surgery.

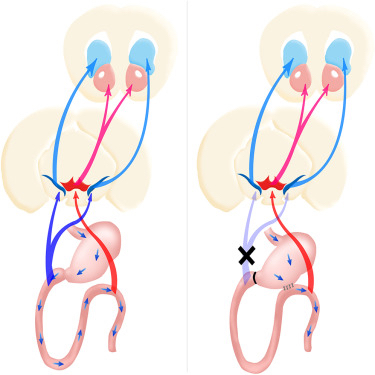

The article notes that nigrostriatal dopamine pathways, one of the four major dopamine pathway categories in the brain, are specifically sensitive to duodenal sugar sensing. The investigators found that performing surgery on mice to bypass the first part of the small intestine, directly connecting the stomach to a lower section of the gastrointestinal tract — thereby bypassing the duodenum, inhibits sugary foods’ effects on the brain’s dopamine reward system that results in maladaptive sweetness seeking.

The article, entitled “Striatal Dopamine Links Gastrointestinal Rerouting to Altered Sweet Appetite” (published online as Corrected Proof 19 November 2015, doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2015.10.009), is co-authored by Dr. de Araujo, first author Wenfei Han, from the John B. Pierce Laboratory and the Yale University School of Medicine, Departments of Psychiatry, in New Haven, Connecticut, and the Laboratory of Oral Biomedical Science and Translational Medicine at the Tongji University School of Stomatology in Shanghai, China, and their colleagues.

The co-authors note that reducing calorie intake contributes significantly to positive outcomes from bariatric surgeries, but the physiological mechanisms linking rerouting of the gastrointestinal tract to reductions in sugar cravings remain uncertain.

They have been able to show that a duodenal-jejunal bypass (DJB) intervention inhibits maladaptive sweet appetite by acting on dopamine-responsive striatal circuitries, noting that DJB procedures are known to directly affect glucose homeostasis by rapidly lowering glucose concentrations in, for example, uncontrolled diabetes mellitus — an effect that requires jejunal nutrient sensing. The researchers found that DJB disrupted the ability of recurrent sugar exposure to promote sweet appetite in sated animals, thereby revealing a link between recurrent duodenal sugar influx and maladaptive sweet intake.

Unlike ingestion of a low-calorie sweeteners, sugar ingestion is associated with significant dopamine effluxes in the dorsal striatum, with glucose infusions into the duodenum inducing greater striatal dopamine release than equivalent jejunal infusions.

The researchers, however, found consistently that optogenetic activation, an advanced neuroscience technique, directly activated the dopamine neural circuit in free-living animals, and observed a striking increase in sugar consumption, overturning the effects of bypass surgery. Mice that underwent this procedure consumed virtually no sweetener following sugar infusions into the stomach, but optical stimulation of dopamine-excitable cells of the dorsal striatum caused the mice to station themselves in front of a sugar spout that released a sugary liquid, effectively restoring maladaptive sweet appetite in sated DJB mice, pointing to a causal link between striatal dopamine signaling and bariatric intervention outcomes.

The investigators conclude that their data provide evidence for a dopamine-centered model linking gastrointestinal rerouting to restrained sweet appetite. They showed that daily exposure to sugar maintains a sweet appetite even after administration of hunger-suppressing intra-gastric preloads, but these effects were abolished in sugar-exposed animals with a DJB. They observe that consistent with striatal dopamine playing a key role in these effects, duodenal glucose infusions induced significantly greater striatal dopamine release than jejunal infusions. Moreover, they discovered that artificial activation of striatal dopamine-excitable cells overturned the appetite-suppressing effects of DJB, with their data placing bariatric surgeries in the context of current evidence favoring a central role for duodenal nutrient influx in dopamine-mediated feeding behaviors.

“Our findings provide the first evidence for a causal link between striatal dopamine signaling and the outcomes of bariatric interventions,” Dr.de Araujo says in a press release. “However, we certainly do not want to give the impression that we have an answer for how and why bariatric surgery works. Much more research is needed in this field … ultimately we would like to help patients lose weight and reverse their diabetes without going under the knife.”

Sources:

Cell Metabolism

Cell Press

Yale School of Medicine